Russia’s Taliban Recognition: What It Means for Central Asia

Recent Articles

Author: Nicholas Castillo, Katherine Birch

07/17/2025

Speaking in early July, the Taliban-installed Afghan Foreign Minister Amir Khan Muttaqi announced that Russia had become the first country to recognize the Taliban as the government of Afghanistan. Russian officials confirmed this fact, and, hinting at likely motives for the decision, stated that Moscow looked forward to working on development, trade, and counter-terrorism efforts with the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.”

Having selectively engaged with the Taliban since their 2021 takeover of Afghanistan, the move will undoubtedly garner attention in the capitals of Central Asia. With Russia having broken any remaining taboo on recognition, the Central Asian states seem likely to follow given these capitals’ own interests in enhancing regional connectivity and countering terrorist groups.

De-Facto Recognition

Despite international outrage at the Taliban’s restrictions on the rights of women and girls, a steady series of events seems to be pointed toward Taliban-recognition across Eurasia. In late 2023 Kazakhstan removed the Taliban from terror group lists, followed by Kyrgyzstan in 2024 and Russia in April 2025. In January of 2024, China accepted the credentials of a Taliban diplomatic envoy, even as it refrained from full official recognition.

Moves such as this are emblematic of what observers term “de-facto recognition,” whereby countries maintain working relations, invest in Afghanistan, and accept diplomatic representatives of the Taliban government without granting formal recognition.

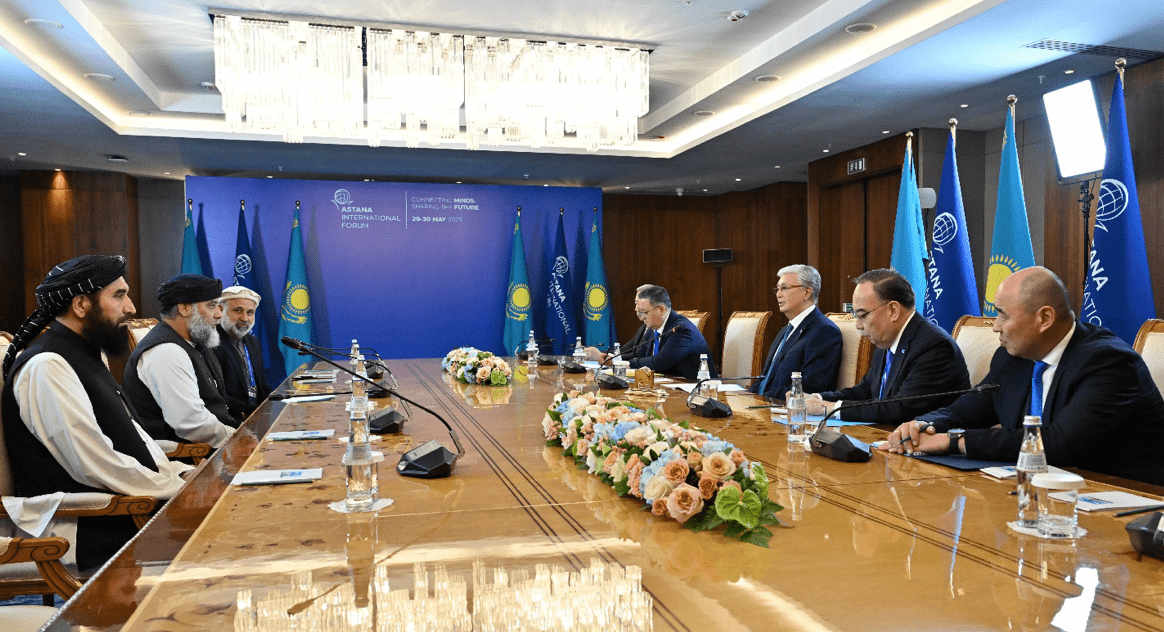

Taliban officials now routinely attend government-sponsored conferences abroad. Taliban officials were hosted at the recent Economic Cooperation Organization (ECO) summit in Azerbaijan and at Kazakhstan’s Astana International Forum in May, where Taliban envoys met with President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev. A week after Moscow’s recognition of the Taliban, Kazakhstan's Foreign Minister traveled to Kabul for a working meeting with the Taliban’s Deputy Prime Minister for Economic Affairs.

Tokayev meets with the Taliban’s representative for trade and industry in Astana, May 2025

Tokayev meets with the Taliban’s representative for trade and industry in Astana, May 2025

The Taliban, in contrast to its more radical governance in the 1990s, has worked to present itself as a more stabilizing governing force, interested in developing Afghanistan and restraining more outward oriented groups in Afghanistan, namely Islamic State - Khorasan Province (ISKP). This approach by Taliban officials is proving effective, with Central Asian states having meaningful interests in developing trans-Afghan infrastructure, managing or extracting resources, and deterring groups like ISKP who are hostile to all governments in the region.

“It shouldn’t be long now,” argues Central Asia journalist and CPC board member Bruce Pannier when reached for comment on the subject of Central Asia Taliban recognition. “Tajikistan will not hurry to recognize the Taliban government,” Pannier says, “but the other Central Asian states are close already. A Taliban envoy [or] diplomat already occupies the Afghan embassy in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Those four might wait for China to announce its formal recognition first, or, for some of the Gulf States.”

Connectivity

For Central Asia, there are major incentives to have a partnership with Taliban authorities. Chief among these are infrastructure initiatives, such as the long-sought Uzbekistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan railway and the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India pipeline (both of which are in early stages of construction) which would provide Central Asia a rail and energy route towards South Asian markets.

Afghanistan is also core to the CASA-1000 project, which seeks to create a shared electricity market by providing high-voltage electrical transmission lines connecting Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. The Afghan section of CASA-1000 was slated to be financed by the World Bank in 2024.

Afghanistan's deposits of critical minerals look to be another major vector for potential cooperation. In a recent interview, the chief executive officer of Kazakhstan’s largest mining firm, the Kazakhmys Group mining corporation, stated that his company was already surveying potential mineral deposits and looking to mine lead-zinc. Uzbekistan has likewise signed multiple agreements with Taliban officials focusing on mining and hydrocarbon exploration.

Counter Terrorism

In addition to infrastructure, high on any Central Asia – Taliban cooperation agenda would be counter terrorism efforts.

Central Asian capitals are likely to consider greater and more direct collaboration with Kabul on counterterrorism efforts to restrain threats towards their governments’ security. The largest shared concern is almost certainly ISKP due to its hostile stance towards all governments in the region. More specifically, Tajikistan’s concern over overtly anti-Dushanbe groups based in Afghanistan such as Jamaat Ansarullah and Tehrik-e-Taliban Tajikistan could incentivize recognition from Dushanbe, who has been hesitant to engage with Kabul.

ISKP has attacked Central Asia directly before, launching rockets at Tajikistan and Uzbekistan in 2022, targeting a region increasingly important for Uzbekistan-Afghanistan trade. The organization additionally sources recruits from Central Asia, some of whom have carried out high casualty attacks in Russia and Iran, hinting at domestic vulnerabilities.

Additionally, Central Asia may want to mitigate more destabilizing challenges associated with terrorist activity, such as illicit drug trafficking, that Central Asian states have historically been forced to contend with.

With region-wide concerns, Central Asian efforts to collaborate with the Taliban on counterterrorism could manifest as a joint regional initiative between Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and even Tajikistan. Such a development would be in keeping with the region’s aspirations for greater autonomy in the security realm, conceivably without the direct involvement of Moscow or Beijing.

Finally, while ISKP has traditionally focused on high body count soft targets, as regional and international actors finance the buildout of new infrastructure and development projects, these investments could create a more target-rich environment within Afgahinstian itself. Attacks on newly minted projects in Afghanistan, especially if funded in part by Central Asian governments, would raise ISKP’s profile and underscore its identity as an impactful actor taking on both the Taliban and secular governments abroad.

This potential change to ISKP’s modus operandi stands to occur particularly at a time when the organization’s operating environment is evolving as Western and Middle Eastern governments become increasingly knowledgeable about ISKP and effective at thwarting its plots.

Yet, Central Asian leaders considering working with Kabul on counterterrorism should be clear minded about the Taliban’s shortcomings as a partner in this realm. The Taliban’s ability to effectively restrain groups such as ISKP might be difficult given its reportedly inadequately resourced counterterrorism efforts.

Remaining Conflicts

There are remaining points of conflict between the Taliban and some Central Asian governments, particularly Tajikistan. Taliban-controlled Kabul may attempt to pressure Dushanbe into withdrawing its overt support for the Tajikistan-based, anti-Taliban National Resistance Front, with Dushanbe in turn demanding the same of the Taliban in regard to organizations operating in Afghanistan. The end result could be withdrawn process that sees Tajikistan left out or late to any regional normalization with Kabul.

Water is likewise a source of potential conflict, with Afghanistan being a crucial source of water for much of Central Asia. Kabul is now pursuing an independent policy that would negatively impact Central Asia. This is best epitomized by the Qosh Tepa Canal, a Taliban project that would divert up to 30% of the flow of the Amu Darya River which provides Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan crucial sources of water for agriculture and hydroelectric power.

Previous incentives to withhold recognition from the Taliban now seem to carry little weight. In an increasingly multi-polar world riddled with conflict and division, the ability of a single actor with a set moral viewpoint to enforce political isolation seems unlikely to hold permanent sway. Major powers, including China and Russia, now routinely engage with the Taliban while the United States and Europe, who had stated recognition was contingent on human rights protection, seem unlikely to spare political energy on the issue of Taliban recognition.

With Russia’s formal recognition of the Taliban, the international de jure diplomatic isolation of the Taliban seems likely to fade. Even if the Central Asian governments wait for other states to follow Moscow’s example first, major incentives for these capitals, whether in the form of counter-terrorism or economic projects that are driving deeper levels of engagement with Taliban officials, with recognition a seemingly inevitable result.